Some 80 harvest seasons have passed since Henry Keppy Sr.’s farm northwest of Davenport basked in the national spotlight and American agriculture took center stage before a crowd of tens of thousands.

It was late October of 1940 when 60 acres of the farmland that had supported the Keppy family — including Henry, wife Anna and 10 grown children — was transformed into the competition site for the National Cornhusking Contest.

While the actual competition came on the final day, Oct. 30, the fun stretched four days beginning on Sunday, Oct. 27, with the dedication of the Keppy cornfield.

“It was a test of who

could do their job the best,” longtime Scott County farmer Glen Keppy said of the contests,

which were very popular in the 1920s and 1930s. “This was the only way corn was picked back then … In reality, they were athletes in the way the greatest sports athletes are today.”

Keppy, now 73, had not been born when his grandparents’ farm hosted the “Rose Bowl of Agriculture.”

But he proudly can retell stories of the historic event as passed down by his grandparents and his parents, Roy and Myrtle Keppy (who coincidentally met during the event). “It was phenomenal to hear my dad and others talk about it,” he said in an interview in his Eldridge home.

Though some details are beginning to blur, Glen Keppy cherishes a scrapbook compiled by his mother of the spectacular event. Filled with faded newspaper clippings, contest advertisements, score sheets and other memorabilia, it is a treasure trove of written history on how Scott County prepared for and pulled off the granddaddy of cornhusking contests.

The county had hosted smaller cornhusking contests and beat out eight other Iowa communities vying to draw what would become one of the largest cornhusking crowds ever.

While contests continued to be held after 1940, Keppy said, “This was the last big contest at my grandpa’s place.”

He added that modernization in farm equipment, especially the introduction of the combine, and World War II changed the face of farming. “There was contsant change in what was happening in America. This was a small corner of the world, but it was a huge event,” he said.

Competition among growers

Henry Keppy’s 60 acres of hybrid corn in Sheridan Township ultimately was selected for the contest field. But a total of four area farmers were in the running for the honor and tasked with planting corn rows that could potentially host the event.

The other sites were: the Grover Hahn farm at Hahn’s corner on Hickory Grove Road; the William Moeller farm northwest of Walcott in Cleona Township; and the Albert Schneckloth farm, four miles east of Eldridge in Lincoln Township.

Nancy Meyer, one of Henry and Anna Keppy’s granddaughters, recalled the other farmers each received rejection letters written on a manual typewriter. Decades later, she received one of those families’ scrapbooks as a gift. Its last entry was the rejection letter.

“It was the biggest sporting event in history up to that point,” said Meyer, whose now late father, Charles “Charlie” Keppy, was 28 at the time. “My dad could not get over all the people and the cars and cars and cars.”

Widespread attention

The national event was preceded by local and state cornhusking meets across the Corn Belt, and enjoyed extensive media coverage. Journalists traveled to Davenport to report for daily and weekly newspapers, regional and national farm magazines and other publications. W.E. “Bill” Drips, of Chicago, covered the event for the National Broadcasting Co. on his National Farm and Home radio hour.

The action also included flyovers by a Goodyear blimp and a dozen airplanes, many of which captured the aerial photographs for distribution nationwide.

Throngs of Midwest farmers and city-folk alike soaked in the good old-fashioned fun of the tent city that filled Keppy’s and his neighbors’ farms. A “circus combined with a county fair” was how one newspaper account described the festivities.

The adjacent Elmer Hamann farm was occupied by food tents, contest exhibits, entertainment platform, a scoreboard and feature displays.

The event spread over the farms of Chas. “Charley” Dengler and Walter Dengler. Even more nearby farms were enlisted to provide an estimated 500 acres of parking.

Site selection

The chance to play host to the 1940 national event was an extreme honor and an economic boon for all of Scott County. In fact, the region’s top leaders in agriculture and business devoted better than a year to planning and lobbying for the contest.

A Who’s Who of Scott County agricultural, business and civic leaders helped establish Scott County Enterprises of Iowa, Inc. to sponsor the contest and handle its business affairs. The new corporation’s officers included J.N. Wells, president, and Chas. Lewis, vice president. Lewis had been the general chairman of the 1935 Iowa cornhusking state meet.

A three-man committee, including Lewis, Farm Bureau county agent Carl Rylander and Davenport Chamber of Commerce’s Henry Dannico, was tasked with studying the management problems experienced by such corn derbies. A local group scouted the 1939 national cornhusking event in Lawrence, Kan.

Ahead of the national matchup, local and regional newspapers followed the contest preparations – as well as the Keppy family itself – in great detail. At the time, Henry Keppy’s sons Charlie and Roy were both active in the farm’s operations.

The 75-year-old Meyer, who grew up hearing the same stories as her cousin Glen, said her father Charlie was a co-owner of the farm at the time. “But he wanted his father to have the honor (of the contest), and he left the farm in his name,” she said. “Dad and Grandpa had to do the planting and preparing for the contest.”

Henry's sons Ralph, Raymond and Roy were active in local cornhusking circles, and early on were believed to be possible competitors for the national title on their own land. Although Ralph advanced to the state meet after winning the Scott County contest in 1940, he placed third and failed to qualify for the national contest.

In addition to Charlie, Ralph, Raymond and Roy, the Keppys had two other sons, Albert and Henry Jr., and four daughters: Mrs. Walter Dengler, Mrs. Norma Meier, Mrs. Ernest Alberts and Anna, then a student at Iowa State College.

“No. 1 stand of corn”

A news clipping, publication unknown, indicated that it was son Raymond who sparked the family’s interest in the project.

Having been in the fields with the contest officials, he remarked at the family supper table that they were having difficulty in finding suitable contest fields. “If we planted our field crossways, it would work out perfect for a contest field,” he said.

After having his corn selected as the competition site, Henry Keppy told a reporter, “I have a No. 1 stand of corn, and I feel sure that there will be a yield of about 90 bushels to the acre.”

Compared to his test field, the elder Keppy said, “The ears are not as large as they were on our stalks last year, but there are two or three good ears to each stand, even though the continued hot weather this summer somewhat hindered the yield.”

Battle of the bangboards

An estimated 125,000 to 160,000 spectators were believed to have watched 21 contestants – representing 11 Corn Belt states – compete for the coveted cornhusking title on that autumnal Wednesday.

“Solid masses of humanity jammed the corn rows between the husking lands to such an extent that it was almost impossible to move about in the field during the contest,” The Register’s farm editor J.S. Russell wrote.

He concluded that it was “probably the largest single crowd that assembled for any one event in the state of Iowa.”

Beginning promptly at 11:45 a.m., the contestants each were assigned four corn rows and were coordinated with a horse-drawn wagon.

“They started at one end of the field and came down to the concessions area, then they turned around and had to go back,” Glen Keppy said. “It was definitely a skilled thing to be good at it, but it was also brute strength and luck. Some people worked a lifetime at the skill.”

Using the tools of the day – a single hook corn husker knife-like tool – strapped to the palm, each man removed ear after ear from the stalks with one hand and peeled away the husks with the other.

As the corn was thrown in the wagon, it would “bang” on 3-foot-high wooden boards attached to the wagon to keep the corn from flying out. The practice gave the contest its “Battle of the Bangboards” moniker.

“A good husker would have four ears of corn in the air at a time,” Glen Keppy said. “One would be hitting the bangboard. Another would be two-thirds of the way to the wagon. One had just left the husker’s hand and the fourth he’d just be picking off.”

“It would take these people just seconds (to pick a stalk clean and bang the board),” he added.

Between the sharp tools and the sheer speed, he said the work “could be bloody.”

1940 cornhusker champ

When the 80-minute contest ended at 1:05 p.m., the wagons were taken to the weighing dock, where judges meticulously weighed the loads – deducting for husk weights and gleanings. The winner was determined by who had the most net husking.

A Times Democrat story reported that the ears were small, but the stalks were short, which helped boost the amount husked.

In the end, Irvin Bauman, a 27-year-old farmer from Eureka, Ill., would emerge as the winner and land himself in the record books.

Bauman, who had been a crowd favorite, was expected by some reports to place third. Instead, he husked 46.71 bushels of corn and not only beat out the favorite, Iowa’s Marion Link, but smashed the previous national record set in 1935 by Elmer Carlson of Audubon, Iowa.

He reportedly brought in a load of 3,550 pounds, but lost 89.1 pounds for the corn left in the field.

Bauman told a newspaper reporter that he won by being “cool in this contest.”

“The other two times I was nervous in the national contests and tried to pick too fast at the start,” Bauman said. “This time I worked at a steady pace and didn’t worry even when I saw that Link had made the turn at the far end of the field ahead of me. I figured if I picked steady and clean I would make the best score possible for me – and if anybody could beat me, let them do it.”

Having competed on the No. 13 plot of land and with No. 13 wagon, Bauman told The Register, “You can’t tell me that there is anything unlucky about No. 13.”

Despite his win, Bauman was not the day’s only record breaker. Five contestants beat Carlson’s longstanding record. The others were: Marion Link, Ames, second place; Ivyl Carlson, Madrid, Iowa, third; Lawrence House, Kansas, fourth; and Ecus Vaughn, Illinois, fifth.

For his win, Bauman received a $100 check and a silver trophy.

Other sights to see

In addition to the signature cornhusking event, spectators moved about the rural fields over four days marveling at displays of farm equipment, including International Harvester’s new models of Farmall and McCormick-Deering machines. The Corn Tent included Iowa State College’s popular display on the history and uses of corn.

Visitors snacked on delicious homemade fare and tasty desserts sold in tents by scores of women and girls from local township 4-H chapters as well as civic and church groups. Five old threshing steam engines were used on site to keep the water hot for coffee. Fresh city water, trucked in by wagons, was served from makeshift water fountains.

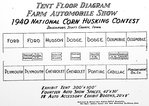

The event also was unique in that it included the first Farm Automobile Show. A horse show featured Scott County’s Roy Curtis and his 20-horse hitch. Cleveland Indians’ pitcher Bob Feller, as well as Wilbur Shaw, a three-time champion of the Indianapolis 500, and 1939 national cornhusking champ Lawrence “Slim” Pitzer, all made special appearances. Feller and Secretary of Agriculture Mark Thornburg served as the contest’s official starters.

The fun even extended to downtown Davenport, where a Halloween Jamboree was held one evening for area residents and visitors.

The Davenport contest also had the distinction of hosting the first-ever International Plowing Contest. It was held on Oct. 29 on a 40-acre field owned by Charley Dengler. Located six miles northwest of Davenport, adjoining the Keppy farm, the site sits along what today is Northwest Boulevard.

The contest was won by an international entrant – Fred Timber, 33, of Stouffville, Ontario, Canada. Contestants, who used tractor drawn plows, were judged on the quality of their plowing. Speed was not a factor.

Action up close

In promoting the event beforehand, Wallace’s Farmer and Iowa Homestead proclaimed in a headline, “You’ll Really See This Show!”

“People are going to be able to watch every husker at close range,” the newsprint publication reported. “They will not have to stretch their necks around the end of the wagon nor strain their eyes through the entire width of the land.”

But for the first time, the competition corn rows were fenced in to keep spectators out and “split so the wagon rig will pass up the center and the husker can be out next to the crowd.”

Despite dozens of guards along each contestant’s corn plot, the crowds broke through for a better view.

“There were so many people around them trying to get to the guy who was doing the best,” Glen Keppy said. “A lot of people ended up stepping on the rows of corn,” which could lead a husker to file a formal complaint to the judges.

In a test of time and precision as well as volume, he said spectators could be a distraction for the men.

Two generations of Keppy men later would prove their own skills at a re-enactment cornhusking contest held in Eldridge in 1970 by the Eldridge Lions Club and Eldridge Jaycees. Glen Keppy and his father, Roy, took first place in the Junior and Senior divisions, respectively, while Ralph Keppy took second place in the senior division and his son Merle won third place in the junior division.

The site today

In 1940, Henry Keppy’s farm spanned 160 acres including the 60-acre contest plot. He also owned an additional 200 other acres.

Today, the now 147-acre farm — where the contest was held — is owned by the Charlie Keppy LLC. It is a corporation including the Meyers, the other Keppy sisters and a brother-in-law. The farm began renting 40 acres for the North Scott FFA Farm plot about three years ago.

Very proud of their Keppy family heritage, Glen Keppy, wife Jean, and Nancy and Ron Meyer have donated cornhusking memorabilia and history to various local organizations.

The Meyers presented a framed newspaper clipping — showing an aerial photo of the contest — to the Walcott Historical Society museum, which opened in 2018.

But Nancy still keeps a few treasures close in their new home in Eldridge. The oldest of Charlie Keppy’s daughters, she cannot part with an old rusty “take-up wheel.” It was one of the wheels of the corn planter her grandfather and father used in planting the contest corn plot.

Just a couple years ago, she also became the proud owner of a piece of memorabilia from the day. One of her daughter’s friends (Shelley Wells McGarry) gifted her a red metal teapot-shaped plaque bearing the National Cornhusker Contest name and a tiny thermometer.

It likely was one of the many souvenirs sold, along with pennants, tea towels and potholders, Meyer said. “I started crying when she gave it to me.”

Meyer, who moved off the celebrated farm 58 years ago (her father lived his whole life there), recalled how she was just 5 when Grandpa Henry died and 13 when her grandmother died.

“But I knew from when I was a little girl, probably 6, that this was a pretty important thing that happened on the farm. It was a big thing for the Keppy family,” she said.